It’s a new school year, and the economy’s on the uptick! With change in the air, let’s try to solve three of the most common legal-writing mistakes.

Mistake 1: The opening of the document is topical or circular, not substantive.

What goes wrong. Although nearly all legal documents start with a “roadmap,” many roadmaps are simply guides to what’s where:

In Part One, I will discuss the pros and cons of settlement.

Still others are circular:

As explained infra, you should settle this case because it is in your best interest to do so.

Why it matters. You’ll draw readers into your writing only if you commit to proving something, not just to talking about something. Starting with substantive points also gives your reader context for the details that follow.

Your action plan. Start by committing to prove three specific points by the end of your document:

As explained below, you should settle this case because (1) juries in this county often grant high punitive damages, (2) discovery will be unusually expensive and intrusive, and (3) three recent product-liability cases cut against your position.

Consider taping the list to your computer to help you stay on track.

Mistake 2: The case discussions sound like the work of a news anchor, not a pundit.

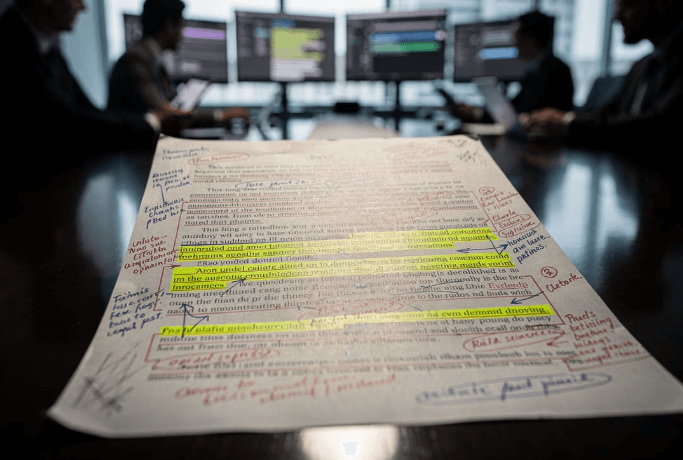

What goes wrong. Many paragraphs announce that an authority is “illustrative” or “distinguishable” and then summarize facts or copy language or both. As Judge Ruggero Aldisert once put it, the analysis feels like “a promiscuous uttering of citations.”

Why it matters. When you use an authority as an end in itself, you force your reader to supply the missing logical links while wading through irrelevant facts and language. The result: The reader feels more confused than ever and skips to the next paragraph.

Your action plan. When it’s time to discuss a case or order, use your own words first to explain how the authority proves the point you’re making today. Only then should you summarize facts or copy any relevant language.

Mistake 3: The transitions are choppy and repetitive.

What goes wrong. In many legal documents, the sentences start to sound the same. They begin with a transition word followed by a comma, and then string together abstract clauses that are long on nouns and short on verbs. The result is too many sentences like this: “Consequently, the success of Plaintiff’s case is contingent upon an affirmative showing of causation.” And too few sentences like this: “Plaintiff can thus prevail only by proving causation.”

Why it matters. You want to push readers through your sentences, not tire them out. Varying your sentence structure will also help keep your readers’ attention.

Your action plan. Every week, add a new transition word or phrase to your repertoire. And experiment with where you put those words in your sentences. If you need some inspiration, here’s my most recent list of 135 transition words that you can use to make your logic clear.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)