In Justice Kagan’s debut opinion, she imagined a debtor buying an old junkyard car “for a song.” Now, a decade later, writing better than ever, she’s penned an opinion about a Ford Explorer.

Leave it to Kagan to adorn this specific-jurisdiction matter with rhythm and punch, intellectual tension, and even a touch of pathos. Looking to sharpen your own persuasive-writing chops? Here are seven ways to ride the Kagan wave.

1. A character-sketch cold open.

The best introductions often boast a narrative look and feel: who, what, when, where, and why. The “who” can be an abstraction—as long as you make it come alive. Here, Kagan creates the character of The State to bookend her pithy opening:

It’s no surprise that Kagan paints the victim—the plaintiff—as a resident of The State, not as a bringer of The Suit, the underlying action that earns barely a cameo here. She does let Ford plead its case in the middle of the passage, though in complex terms that make it seem like the defendant is trying to wiggle away from The State. Also note how much this passage looks like a readable tale. Kagan even does the unthinkable, at least for many members of our profession: referring to “Ford Motor Company” as “Ford” without a single “hereinafter” or defined term!

2. Take your opponent’s arguments seriously, if not literally.

In briefs, many attorneys can’t stop making the obvious point that they disagree with their opponents. Are our opponent’s arguments so seductive that we need to keep telling readers to cover their eyes lest they give in to temptation?

Show some confidence, Kagan-style. She offers a great model of how to seem almost generous to your opponent even as you pull the wording strings behind the scenes.

3. Combine punchy sentence-openers and varied sentence structure.

Justice Kagan consistently earns the highest BriefCatch writing-quality scores of any living Justice. She strikes the perfect balance in persuasive writing, with passage after passage as logically tight as it is easy on the eyes and ears. How so?

Like Holmes and Jackson before her, Justice Kagan starts many sentences with one-syllable words that propel the prose forward. At the same time, to avoid a staccato sentence pattern, she spices up her sentence structure with dashes, colons, and the occasional mid-sentence aside.

* * *

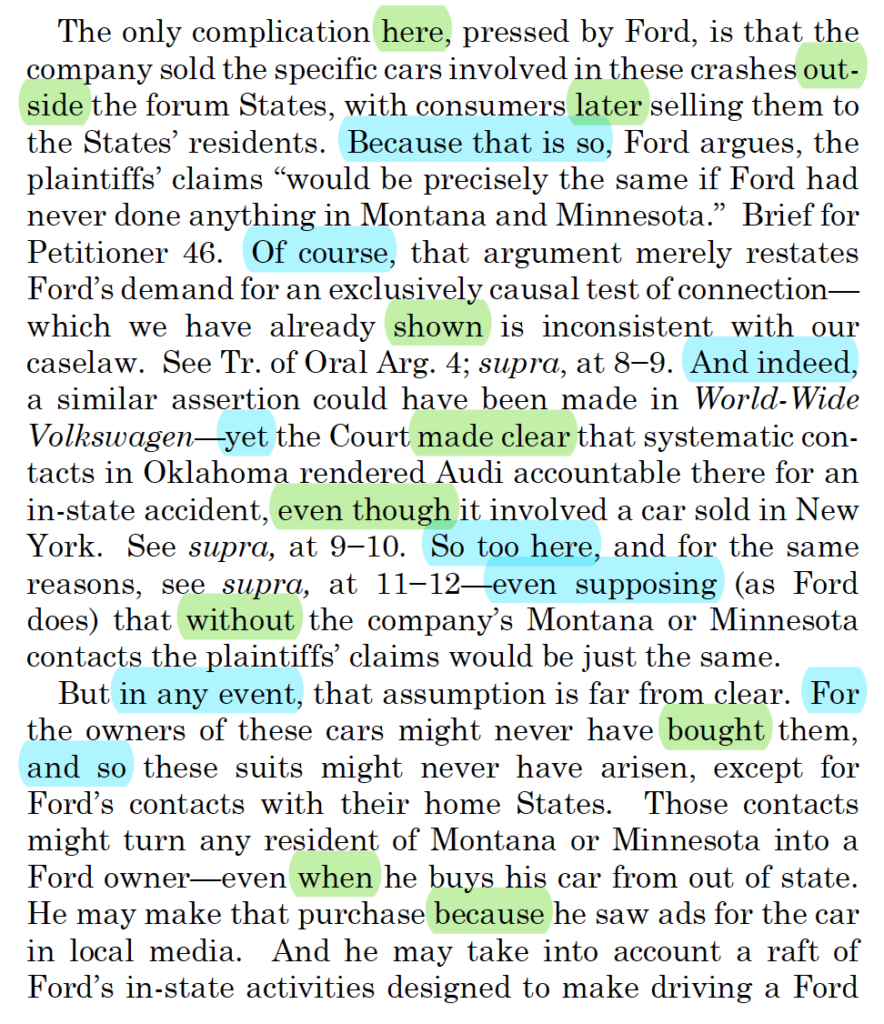

4. Combine complex logical and direct language.

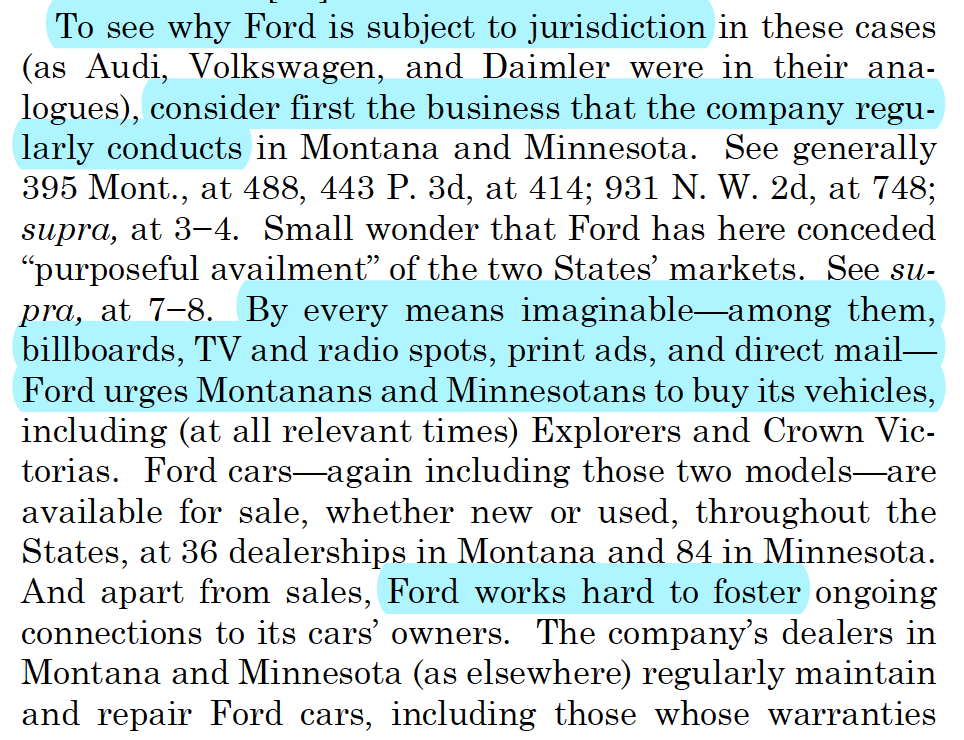

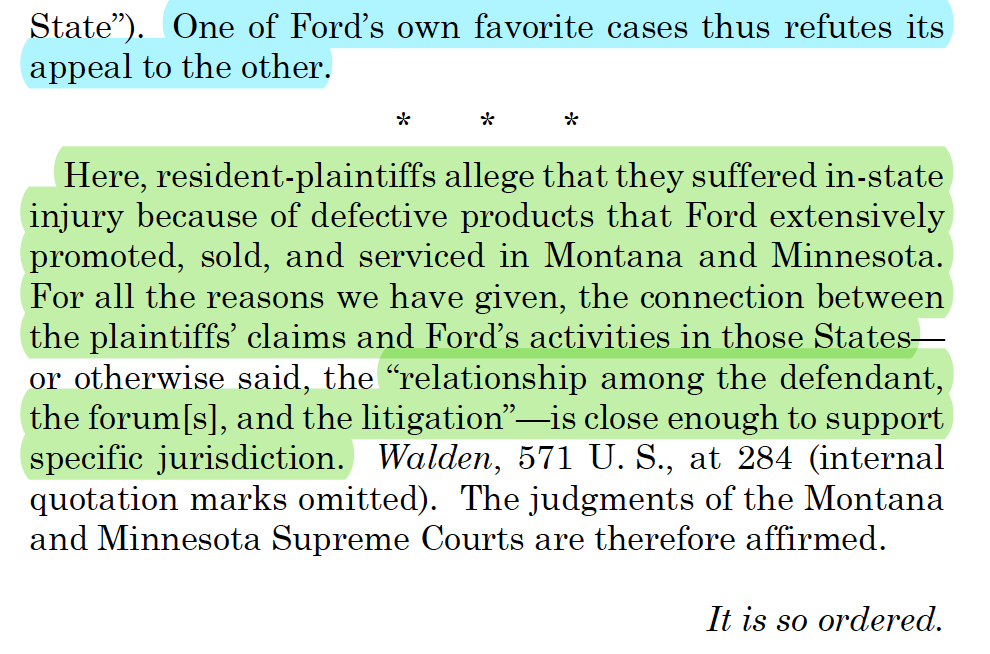

Another great juxtaposition to stage: intricate logic reflected in diverse transitional devices (in light blue below) against concise, modern, direct word choice for the rest (in green below). Not “in this matter” but “here.” Not “outside of” but “outside.” Not “subsequently” but “later.” Not “demonstrated” but “shown.” Not “instructed” but “made clear.” Not “despite the fact that” but “even though.” Not “in the absence of” but “without.” Not “purchased” but “bought.” Not “due to the fact that” but “because.” Not “even where” or “even in the event that” but “even when.”

5. Consider the source.

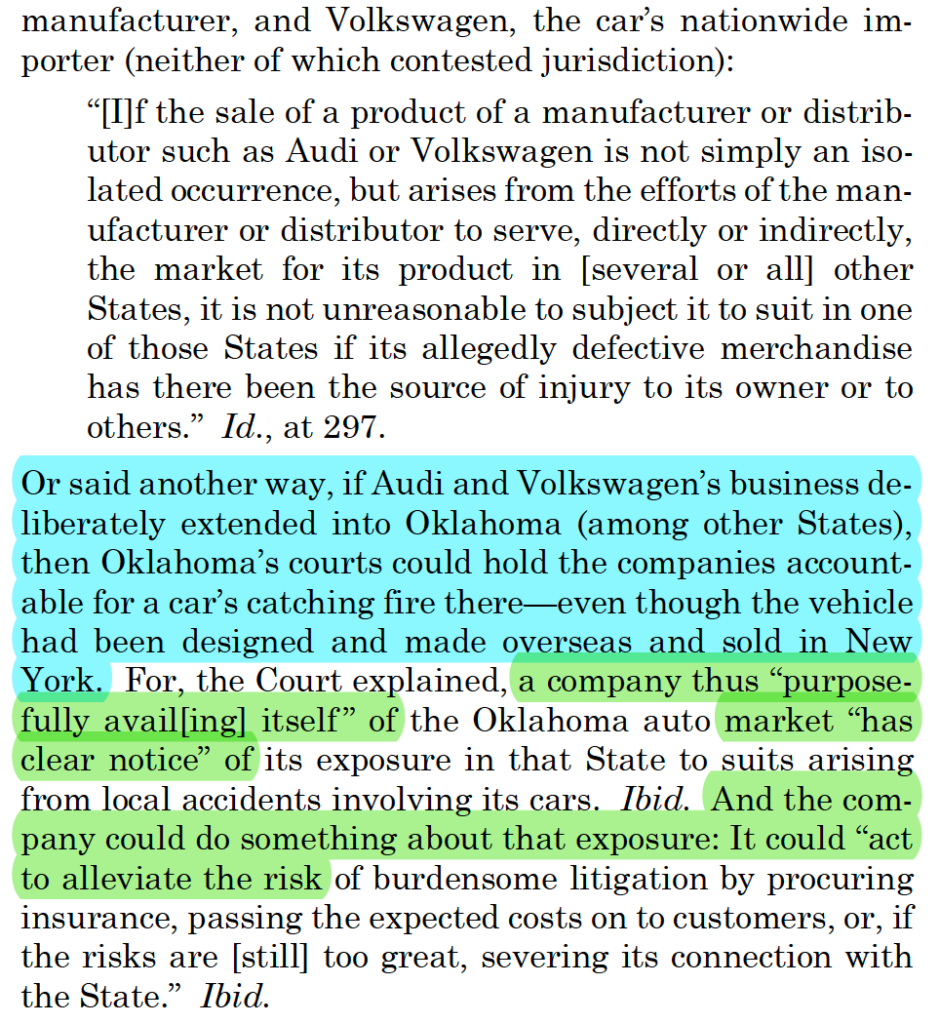

You can include the occasional long quotation or extended case discussion with pride—but “that does not mean anything goes,” as Kagan puts in on another topic here.

Recast your citations. Intersperse your own commentary. And favor snippets of quotations over complete sentences.

6. Get real.

Relish the chance to explain why a doctrine works the way it does or why an outcome brings a pragmatic benefit. Here, Justice Kagan makes jurisdiction seem righteous, and not just right.

7. Conclude with aplomb.

Many great briefs and opinions have two conclusions. First, the conclusion to the last bit of analysis (marked in pink here). And then the grand conclusion, which can reprise themes and even leave the reader with a quotation saved for the glorious end.

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)