Legal AI Trusted By Top Firms and Judges

.svg)

.svg)

Better Writing. Stronger Firm. Immediate ROI.

Work smarter, write faster, and deliver more persuasive documents—without compromising confidentiality or control.

Reduce editing time by up to 50%, freeing you to focus on high-value tasks and improving overall productivity.

"BriefCatch is a fantastic tool. It made me aware of bad habits I didn't even know I had. Editing is faster and my briefs read better."

“The more often you use BriefCatch, the less you need it. The suggestions it makes become second nature. This improves your overall writing and saves a ton of time.”

“In seconds, BriefCatch can perform a strong first-round edit that would take me an hour or more to perform by hand."

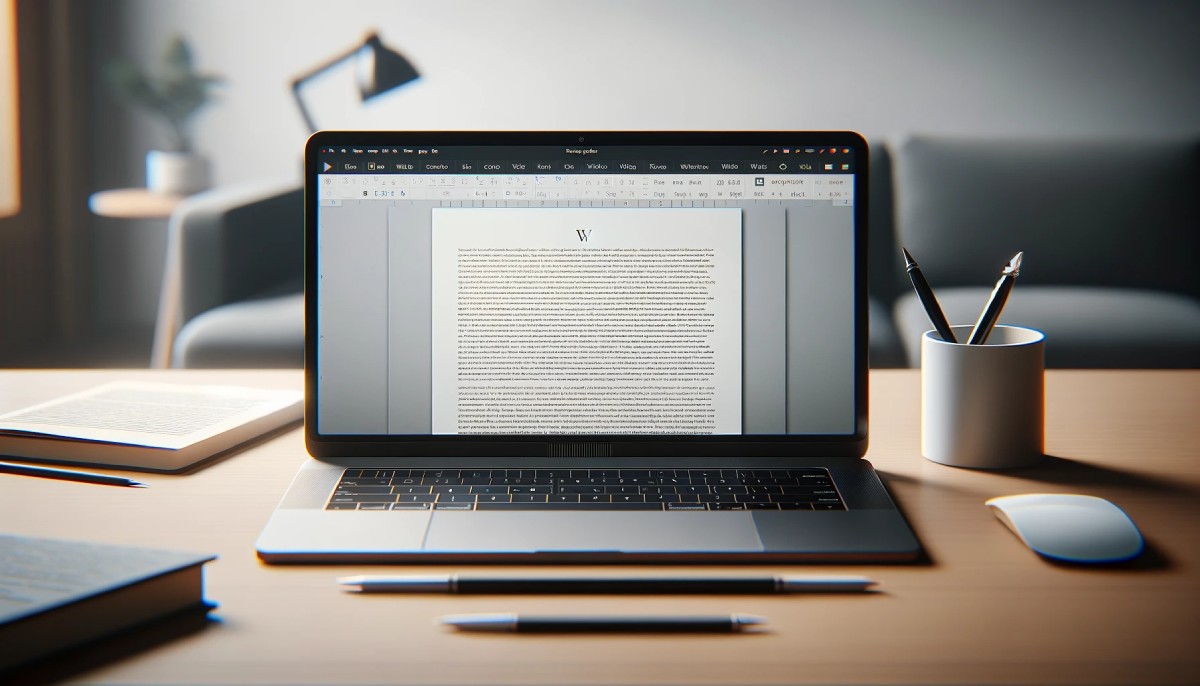

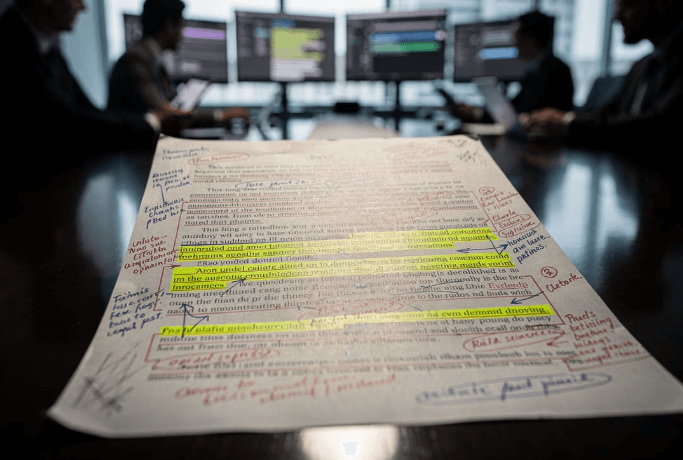

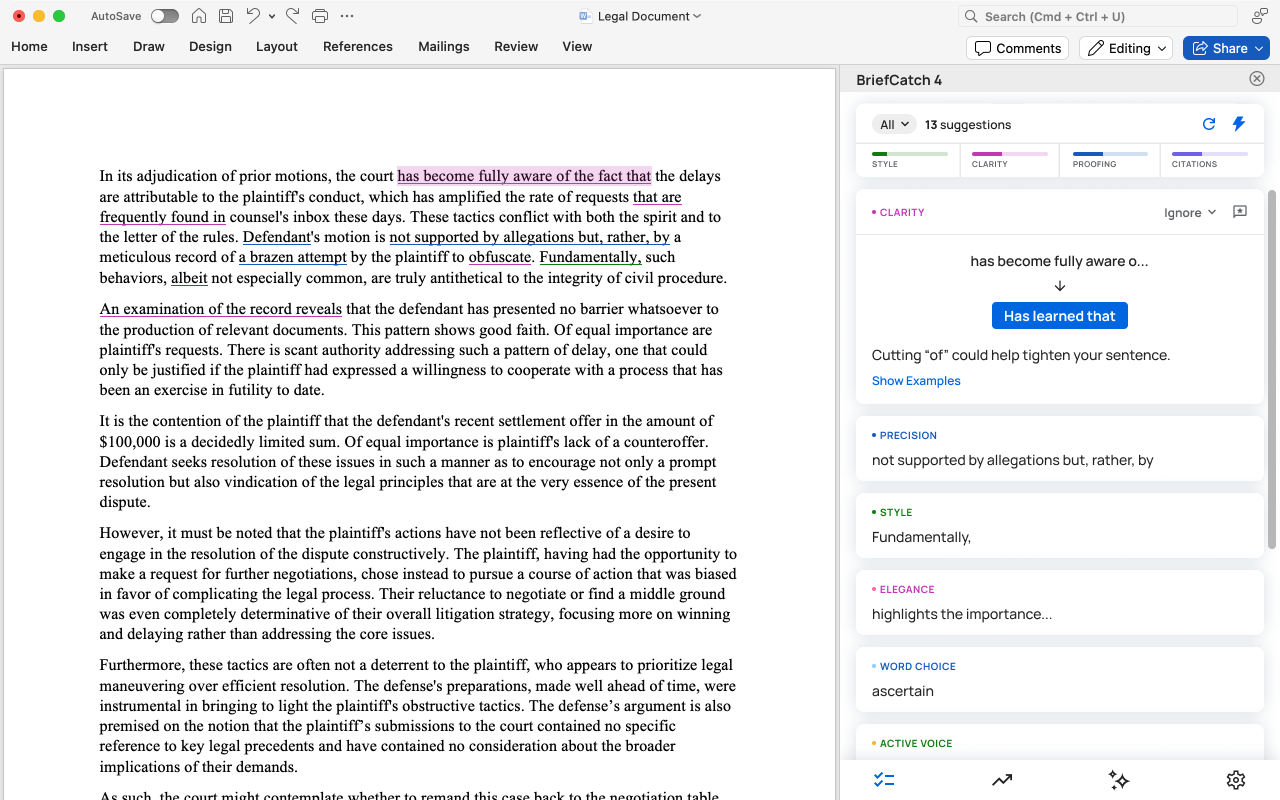

Built for How Lawyers Work—Directly in Microsoft Word

BriefCatch installs in minutes and runs natively inside your existing systems. It enhances the legal writing you already do—memos, briefs, motions, opinions, and contract drafting—through advanced legal AI and natural-language processing.

.svg)

.svg)

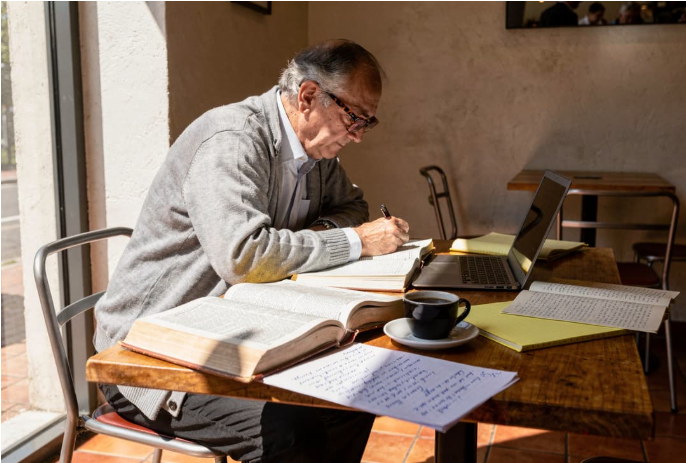

Built on Expertise, Not Generic AI

Every rule and recommendation in BriefCatch Next reflects proven techniques from thousands of elite legal documents and judicial opinions, never scraped internet data.

Developed by Ross Guberman, author of Point Made and Point Taken, rules are formed by decades of legal research and courtroom analysis, grounded in authoritative content from real filings and opinions, and tailored for law firms, courts, and legal departments.

This is AI legal intelligence designed to complement, not replace, human judgment.

.svg)

Security and Data Privacy by Design

Lawyers handle sensitive client data daily. BriefCatch Next is SOC 2 certified and operates fully within Word—no uploads, no servers, no risk.

Unlike generic AI chatbots, BriefCatch Next protects privilege at every step.

.svg)

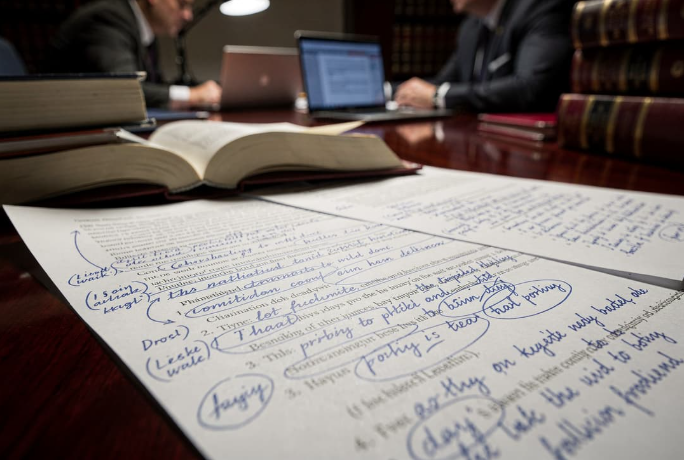

Smarter Training. Stronger Teams.

BriefCatch Next doubles as a digital writing coach, surfacing actionable insights and reliable feedback that accelerate associate development.

- Reinforce firm-wide style and reasoning

- Shorten the learning curve for new hires

- Turn daily drafting into continuous learning

.svg)

See ROI From Day One

At less than one billable hour per month, BriefCatch pays for itself with your first filing—and keeps compounding returns. Replace repetitive tasks with intelligent automation, reduce human error, and free lawyers for strategic advice.

That’s the best AI application to real-world legal writing.

Each feature helps your team work smarter, cut manual review, and drive better case outcomes.

Legal AI uses natural-language processing to improve legal documents directly in Word, cutting errors and speeding up review.

Yes. It’s SOC 2 certified, installs within Word, and never stores or retains content.

Absolutely—it streamlines contract drafting, document review, and due diligence while fitting seamlessly into law firm operations.

Each edit delivers authoritative content and gives context for every edit, reinforcing skills with every draft.

Bowman and Brooke LLP significantly enhanced their efficiency and document quality, maintaining their leading position in defense litigation.

True numbers,

exceptional results

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

Experience the Power

of BriefCatch

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)

.svg)